Rose Harbour, Hadia Gwaii, BC, Canada, 3-JUN-2018 – We’ve been in Haida Gwaii for twelve days. Six of those days have been spent waiting for weather to pass. The two days before we crossed Hecate Strait we spent waiting for weather, so by my count, eight of the last fifteen days have been spent waiting for suitable weather to travel.

We waited four, may be five days in Sandspit, where we met people, made friends and traveled up to the top of the north-most island in Haida Gwaii.

Haida Gwaii is a nexus of beauty, people, commerce, history and politics.

The Haida are the native people who live here. Like most of the indigenous people of North America, only 5% survived the europeans. While we have been traveling in Canada letters from a 19th century British Columbia governor have been discovered that detail his successfully executed plans to kill off the native population with smallpox. A technique that was used in other parts of North America with equal success.

The Haida have lived here since before the last ice age. They were a successful people who had a complex matrilineal culture that traded with peoples outside their regions, created much art, warred, kept slaves, and all of the other things that well-rounded cultures have always done.

In the 1980s, as most Canadians my age will remember, Haida people blocked logging on Lyell Island, just north of here. A agreement was reached and much of the southern islands were turned into Gawaii Haanas national park. Some of the land was set aside for Haida people, but the vast majority is undeveloped park land. It is not reachable by anything other than plane or boat and there is no ferry service.

The remains of five Haida villages are manned by Haida people, called Watchmen, who are paid employees of the Park Service. The first site we visited, Koona, aka Skedans, were manned by a married couple, Didi and her husband. Didi is Haida, her husband is Canadian of Dutch descent*.

Didi was very much into the spiritual side of her people.

The villages we visited were abandoned after the small pox epidemic left so few people alive that the only viable survival approach was for the groups to move to a single location, Skidegate (Skid-ah-Git). A smaller group moved to Massett, and third group moved to Hydaburg in Alaska, more threads of our journeys come together in Hydaburg.

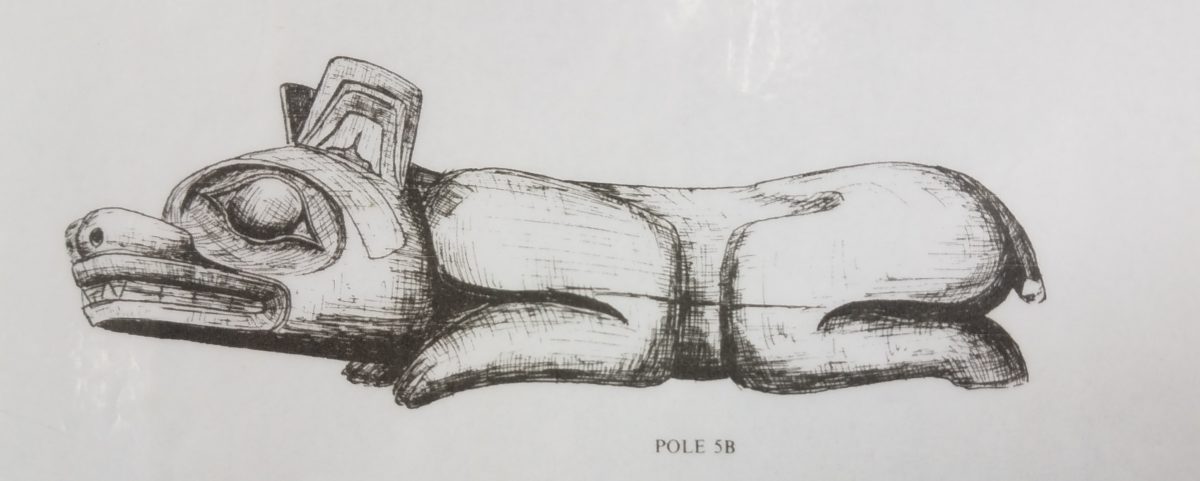

The villages left behind are crumbling in keeping with the tradition that fallen totem poles be allowed to return to nature.The people we meet are Haida, but genetically they vary from 100% First Nations people, to red-haired and blue-eyed.

The Watchmen we meet are all from Skidegate or Massett. Some have lived in Haida Gwaii all their lives with small exceptions for schooling, while others moved away to Vancouver, Victoria or the Alberta oil fields and have returned.

The conversations we have roam from the prepared talk to their own personal histories.

What is so very different from other native people we have met in the US, is that this is all so recent. These are not people whose ancestors had this happen to them, it is them and their parents and grandparents. First Nations people in Canada were not given the right to vote until 1960. The last residential indian school was closed in the 1990s. (It is the school in Alert Bay, I think. The community inter-generational trauma still lingers.)

The population of Haida people is small, less than 5000.

The recentness of this, once it truly dawned on me, changed everything. As a big-city kid (Toronto, New York, San Diego, Atlanta), all of the history of native peoples has a distant, mythical quality. Here, it finally sinks in that the people I am speaking with knew the people to whom much of this happened.

And yet, these are fully 21st Century people. But that also is Haida.

The Haida, when the europeans arrived, had copper from trading with inland people, and iron and more copper that they retrieved from Japanese fishing vessels that would end up on the shores here. But they had no ability to smelt or forge tools.

The Haida were not a peaceful people. They warred and built war canoes using a technology that they were very careful not to allow others to learn: they were so good at keeping their technological advantage that other peoples would not fight Haida on the water, instead making the Haida come ashore to fight where the technology was more evenly matched.†

An illustrative story is of an American ship that fired on a Haida village and then turned tail when the Haida village returned fire with cannons they had acquired through trade. Haida war canoes became armed with swivel guns.

Not mentioned on any of the tours were the Haida forts that impressed the Europeans. The Haida would capture entire ships and trade them back.

Haida villages, when we became alert to the settings, were placed where they could be easily defended. A Haida house entry requires one duck down through a small entrance. As each guide pointed out, hostile intruders could be repelled with a club against the back of the skull as they entered the house.

Haida would raid Haida taking slaves a means of increasing wealth. Slaves could be traded or given away.

Slavery, as one of the guides pointed out, was not like the slavery of Africans. Slaves were the same people and one’s position as a slave was mutable. A woman slave instantly became a high-ranking member upon marriage to a chief. In a matrilineal society, this is a move from the very bottom to the very top.

The tours are of the villages and the remaining ruins. Because the ruins are allowed to return to nature, there is no attempt at preservation. Everything is rotting away. See it now while it still exists.

Each watchman told a different view of the village and Haida life, past and present until a three dimensional picture came into view.

As we started to get a picture of the various Haida villages, they each acquired a personality: the fabric of Haida Gwaii started to appear. Didi told us that her people were friends with everyone and they did not war with any of the other villages. But, as the conversation continued, it became clear that her village was a market where all groups, Haida and outsiders, came to trade.

We also found, as we spoke to some Haida people, that their conception of time was different than Jennifer’s and mine. Sentences in the present tense and discussions of family might span generations. Membership as a Haida has a much greater depth and web of connection than anything Jennifer or I know.

Over the weeks, we came to know the charter boats working the park, and from reading the guest book we came to understand how rare private vessels from outside Haida Gwaii are.

I feel some ‘‘cognitive dissonance’’ here. It is something that has overtaken me across these three years. Living in a big city amongst many, many people is starting to feel unnatural, may be unhealthy is the right term. I think that part of it comes from being away from all the marketing that has told me, across my life, what is desirable and what I should want.

We meet people. Local people and people traveling. So, we are not alone. The people are people just like anywhere else with their personalities and eccentricities, but the lack of concentration of people, and what is argued as the slower pace, is gravitational.

When I think of the current-day Haidas I meet, they are gentle, thoughtful people.

Thinking of the warrior people that some Haida villages were, I think of the reason for war and the luxury of war. Like the warrior, slave-trading people of Mesoamerica, the Haida were rich people who needed to spend little of their time gathering sustenance.

Haida raided other villages to increase their wealth. Prestige was gained by giving away wealth, but giving was not really giving at all. By accepting gifts at a potlatch‡, the receiver entered into a contract to truthfully tell the story of the potlatch.

Subsistence people do not have time to war.

A common clause used when telling a story of the past is, ‘‘I am told that.’’ That stories may not be accurate is part and parcel of the Haida creation stories. There are different versions of the stories and the stories are told as just that: In one version of the story, something happens. In another version of that story, something entirely different happens. There is no attempt to reconcile the stories. The two stories are accepted. As an outsider, I can’t tell what the feeling is, there is no apparent need for reconciliation or a hunt for the real story, as I instinctively look for.

There are a number of incongruous images to reconcile when we leave Haida Gwaii: The image promoted by the current-day Haida that emphasizes artwork, the poles, the community and family. The warring nature of the Haida, which no Haida we met hides nor makes apologies for, is not part of the promotion. The current Haida are paradox.

In old Massett, we saw modern house upon house abandoned and near falling in. A man we met told us these houses were given to Haida by the Canadian government and fell into disrepair because they were not valued; drug use was high in that area. It was the view we sometimes have of American Indian reservations, while 40 km away is Skidegate, where everything seemed in good repair and all was well.

All of this is surrounded by great beauty in a setting scoured by vengeful weather.

*There are a remarkable number of people of Dutch descent in BC.

† This meant that there was no defense against a Haida landing. https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/haida/havwa01e.shtml

‡ A potlatch is a large gathering that serves many purposes including matters of governance, celebrations and marks cultural and family events.

The current term of ‘potluck’ comes from ‘potlatch’. It is used to describe bringing food to a get together – we often have potluck dinners when relatives get together.