Today is the three-year anniversary of my Dad’s passing. I initially wrote this in the days following his death intending to publish on the anniversary of his passing. Life, as it does, got in the way. I wrote and edited portions in April 2021 at the Rocky Point house, the house I grew up in, preparing it for rent, reviewing the artifacts of a long life, and in quiet moments… just sitting and thinking. Time does not rest and months and now years have passed. I have left the dateline to match the day I started writing this.

Rocky Point, NY, 31-DEC-2019 – The first time I realized my father wasn’t perfect the world tipped on its axis. I can’t remember when it was, exactly, but I was an adult. A young adult, but an adult. I remember what I understood at that point in my life, my world view and my sexual experience, all of which frame a time.

My father died this past Sunday morning at Stony Brook Medical, as they are calling the university hospital these days. His heart stopped. It was related to blood thinners, with the nursing staff saying he must have clotted from too little thinner, and the on-duty MD saying it was internal bleeding from too much. Does it matter? He’s dead.

My dad loved airplanes. Born in 1927, he loved the airplanes of his youth and young adulthood. Last night my brother Ken (I have three brothers) and I were watching a BBC documentary on the Spitfire. As questions arose and I expected to have them answered by my dad, I finally realized that he would not be coming back.

My father was the second of four children and the child of a physically abusive father. As I became aware of such things, I could see the manifestations of such: being a second child behind a light-eyed, handsome boy.

The retired adult version of my father dominates my immediate memory of him. He was at all stages of his life natively intelligent, brilliant many people say, but trapped in the worldview and horizons set while growing up, as it was for me and I expect most of the world.

He was the child of immigrants, his mother arriving at age 17, and his dad at age 8. I think about how the world viewed him. People who looked like him, but were a generation older spoke English as a second language. I lived in NYC during a large influx of people from India and Pakistan. When I started meeting their children a generation later I was fascinated at my own expectations of an accent from these accent-free young adults and that these young adults were analogues of my father (and my mother) a generation earlier.

My father was a Manhattanite from East Harlem in a neighborhood that was Jewish and Italian when he was growing up. The building his parents moved into, ‘‘in the block,’’ was on the north side of 117th street between 2nd and 3rd avenue. The apartment was a fourth-floor walk-up. The building had a marble entranceway and marble stair treads. Success, upon growing up, was moving away, out of the city or farther. My earliest memories of that neighborhood are from the early nineteen-sixties. The fortunes of the neighborhood had changed, as had the ethnicity of its residents. It was now mostly black in my memory, with black teenage girls and boys listening to Motown on transistor radios and coming with curiosity to meet my grandparents’ Canadian grandchildren who lived in faraway Toronto.

When I laid out how I would write this piece, I segmented my father’s life into three chronological slices, instead, I see his life as parallel threads against a life calendar. I only see his life as a son does, and as a first son whose lessons were different than his siblings, by being first, certainly, and perhaps by the age I was when my father abruptly abandoned the American corporate dream plunging my family from the upper band of Canadian society with an unbounded future for his family to life of a forty-year-old New York City school teacher living in a house provided by his father in summer town where many of the full-time residents were on public assistance (welfare in the parlance of the time) and college wasn’t on the horizon.

My grandparents owned a delicatessen on the southeast corner of 117th street and second avenue in Manhattan, half a block east of their three-bedroom apartment where they raised my dad, his two brothers and his sister, Marie, who being the only girl, had her own bedroom.

My father, like his siblings, worked in the Deli after school and on weekends. He played handball and won school medals. He was, growing up, fat, and after he returned to the US from Canada, was fat again. He always had a humorous view of his childhood. He was by our standards today physically abused, though never struck hard enough to be physically injured.

He was fascinated by airplanes, built models, and read the popular aeronautic magazines of the time.

During the war, his family, being in the food business, was unaffected by rationing, but the neighborhood was mafia controlled and the business paid protection. When I was in my twenties, I sat with my father’s mother, Clara, while she told me about protection. They paid money and they had to buy products that were not fit for sale. Once, she told me, a rival gang came in demanding protection, as well. I asked her, what did you do? She replied, I told them I was paying protection, come protect! What happened? They sent some men to be in the store when the other gang came to collect. And then? The other men never showed up.

As I grew up, my dad told me the story of being in the barbershop in the same block as the deli when the man in the chair was shot to death. The story fleshed out as the years went by as each man in the story died. In the last twenty years, the story was completed when I learned that the shooter was the barber’s son.

Nick, my father’s elder brother’s trajectory changed with the war. A lady killer, with light eyes, curly hair, which was the rage (see pictures of Eddie Fisher), failed his military physical after a large going away party, and eventually failed out of college. When I was in college, I found his diary from this time, which was much too close to what I was experiencing – though I did graduate.

Rather than becoming the educated family leader of the next generation, Nick worked in the store.

My father attended Benjamin Franklin High School. He enlisted in the army after high school, was sent to some military training as the war was winding down and at age 19 became part of the occupation force.

During this time he learned about women, I may have a half-sibling somewhere in Germany. The woman may have been pregnant, and my father might have been the father. I only learned about any of this after my mother passed, when my dad was in his eighties.

But, my father’s internal self would show itself during these miltary years. Fistfights that left the wall the other man eventually leaned against, splattered with blood; as a private challenging an anti-immigrant sergeant to a dual, and learning the limits of the command abilities of a wet-behind-the-ears nineteen-year-old buck sargeant who has been given battle-hardened German troops.

He returned home, went to NYU on the GI Bill, and met my mother, who was the secretary to the head of the Bio department and engaged to the department head’s son, or so the story goes.

Who my parents became and how they became it, becomes the confused tangle of influences, perceptions, and goals. To my father, my mother was the height of sophistication. She was two years younger, nineteen to his twenty-one, but was sophisticated, having been to restaurants and knowing the rules of etiquette. But then it becomes confused. My dad’s mom came from some money, she arrived on her ship first class, and taught me the rules of restaurant dining in Naples before she came to the states.

My parents married in May 1953, I was born in July 1954.

By then some of the dynamics of his family had changed and my parents’ disparate tastes and cultural interests could be seen, if not at the time, certainly in the photographs of that time and in the stories my mother told me.

Pictures of my father’s family with my mother before they were married often show my mother as the center of the activities. She loved my father’s father and shared cultural interests with Nick. Disturbingly, in the pictures, Nick looks to be in love with my mom with his arm always around her and his eyes always on her. My dad looks confident, as he should be, and oblivious. Nick would eventually marry a woman who looked startlingly like my mother and form a disastrous marriage.

Once married, my father’s career would leak the personality of the man who challenged authority by frequently quitting jobs without another lined up.

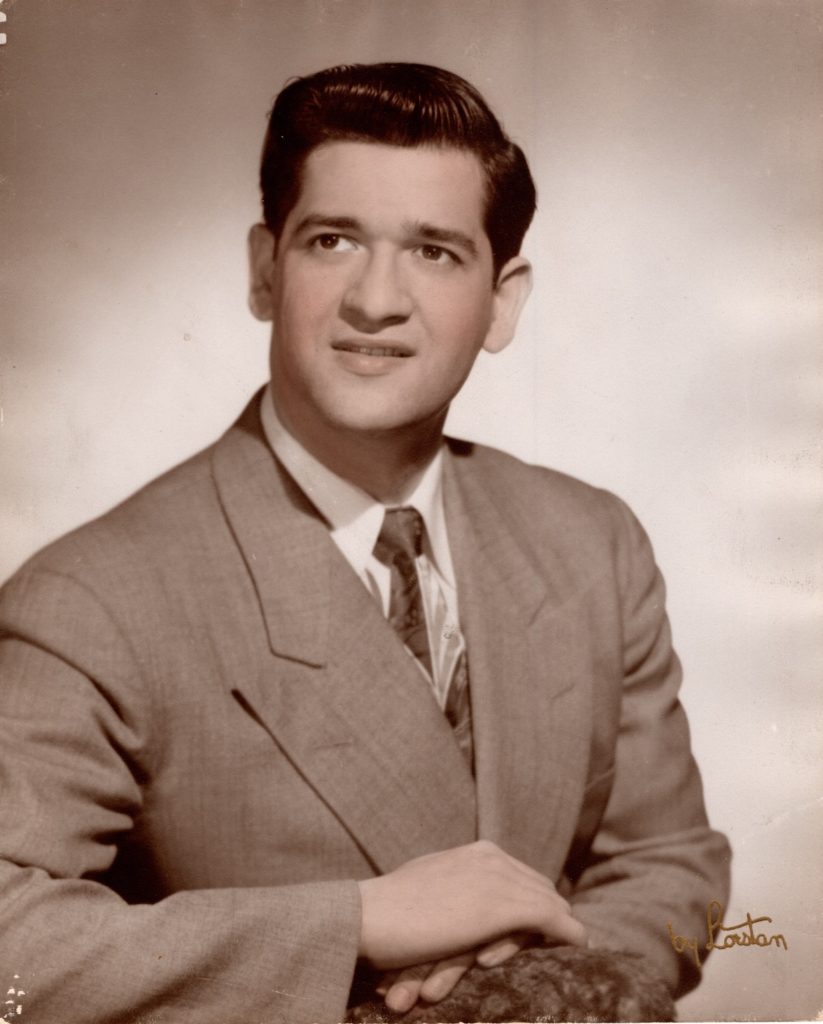

My dad had very good social skills, he made a great appearance, looked good in a suit. By now, the straight black hair of Desi Arnez was popular, with starched collars and french cuffs. He had success as an ophthalmic-drug salesman, a detail man. He wasn’t a natural sales guy, he was a good sales guy. He cared about his customers, he cared about his company and he made sure he did right by both.

Alcon, which is still in business and makes very shelf-visible contact lens products, was a young company out of Fort Worth, Texas. Founded by Mr. Connors and Mr. Alexander. The company sent my dad to Toronto to open Canada as a territory. It was the life my mother dreamed of.

In Toronto, they were educated: In Toronto, in the 1950s, having a college degree set one apart. My dad’s customers were MDs who would come to the house in Don Mills for parties. There was money for restaurants. My mother taught us manners and dressed us well.

My dad was building out the territory, initially being gone for six weeks at a go, covering the 4000-mile-wide country by car, seeing every ophthalmologist in the country personally. Eventually, with the effort yielding results, we moved to a five-bedroom house in a new development in Willowdale, my dad hired salespeople, opened an office, and hired a secretary.

Alcon decided to build something larger and hired a Swiss executive over my father and then it all crashed. My dad quit rather than submit to this man’s management, or perhaps the management was designed to drive my dad out. The reason is lost, but my dad quit (or was fired depending on who is telling the story*) with no other job in sight.

I asked him, forty some-odd years later, why he didn’t take a job with a competitor. His answer was simple, sincere, and demonstrated the man. How could he work for another company when he told his customers, who trusted him, that Alcon’s products were the best? He would go so far as to tell his customers to buy a competitor’s product when he felt the Alcon offering wasn’t up to snuff. Trust was what it was all about.

With no job, five kids between ten and one year old, my Dad returned without us to New York to work in his father’s deli. The crash was complete from the highest levels my mother could dream of, where leaders in the Canadian field of ophthalmology were dear friends and used my mother as a confidént to, after more than a year apart, living in a town which was mostly empty summer cottages and many of my classmates were on welfare.

New York City had a teaching shortage at the time. At age forty, my dad became a New York City special-Ed teacher: The next segment of his life and one which would change all our lives.

As a child, years are momentous in their duration. Hell, at age ten, one year is ten percent of your entire life. It is a sixth of your cognitive life and once you hit puberty, each year is an entirely new life.

Rocky Point elementary school was confusing, frightening and I didn’t fit in. It was populated by all the kids my mother seemed to want me to stay away from. This was the US, a place I was from and had romanticized, but the values that I held were the values rejected by the very visible dominant kids: reading, being smart, doing good work. And to a very large degree, looking back, the educators weren’t competent and didn’t know what to do with me. This carried forward: In the early 2000s, thirty-five years later, the next town over still had two-and-a-half times more graduates going to a four-year college than did Rocky Point.

I must have scored high on some standardized test because suddenly everyone was counseling me to do better in school and telling me how smart I was. But nothing changed, no one worked with me to develop whatever amazing intellect they thought I had.

We had moved from a space where everyone in my parents’ social circle and neighborhood was on an upward trajectory to a place where bragging rights belonged to whoever could do the shoddiest job and get away with it. Later I learned that many of my teachers were alcoholics.

My dad moved from school to school within the NYC system working for a number of years at Saint Mary’s Home in Syosset, which was run by Catholic Charities and had an NYC school on the property.

Because the Long Island communities were so small, my high school was four towns west of Rocky Point in Port Jefferson. In Port Jefferson, I returned to the people I knew in Toronto, well educated, well spoken, who valued what I valued. I was home.

My dad, to support five kids and a stay-at-home spouse, worked two full-time jobs. I started working part-time at age fifteen by lying about my age. It started my capacity for crazy long hours and no sleep, which would characterize my professional career and be perfectly suited for passage-making.

My dad’s life must have been a weight that I can’t imagine, full of frustrations and without a horizon or star to steer by. He had built model airplanes and models of other types in Toronto. They were an activity that could travel with him and be worked on in hotel rooms. We would go with him to fly his free flight models – radio-controlled was the province of really rich men.

He lived somewhat vicariously though us, getting us into hockey in Toronto: I was a disaster at it; my brother Vin was a star.

In the late 1960s, I remember my dad in a fit of despair smashing the R/C model that he had not completed in the years since we left Toronto. In 1972, he got me a full-time job at Saint Mary’s, so I worked full-time third-shift and attended university full time as well.

He put Vin and me into boy scouts. The scoutmaster was Harry Ackerman, who was wonderful with most boys. He was a master mechanic at Pan Am, a rough and tumble CB during WWII in the Pacific theatre, and a kid from Hell’s Kitchen in Manhattan. Harry had no idea what to do with me; I was very disappointed when he valued boys who had skills and horizons that I didn’t value and couldn’t understand.

The time at St. Mary’s came to an end. I was in college, had found the woman I would marry, who was brilliant but injured in a way beyond the ability of a 19-year old to understand, who would adopt my parents and especially my father as her own.

In March 1977, my mother was in a seemingly insignificant, when viewed from the outside, car accident that left her a C4 quadriplegic. My father’s dedication to my mother and his astounding capacity to support divergent, seemingly impossible responsibilities came to the fore.

He worked full time, or was it two full-time jobs, oversaw my mother’s care, and kept her alive. His devotion to my mother was complete, but it left my three younger siblings to raise themselves. I was married and working on a career – 70 hour weeks were the norm, my brother Vin was working. I wonder now, was I a good son in that period? My mother spent more than a year at Rusk on second avenue and 32nd st in Manhattan. Did I visit her as much as I should have? The hospital staff worked with my dad and brought her to the UN Chapel when Robyn and I were married there.

When I was 13, I learned to sail at Boy Scout Camp Tuscarora near Binghampton on the NY state, Pennsylvania border.

My dad fostered this, or did he live through me? I built a sunfish-style sailboat from Popular Mechanics plans when I was fourteen. I bought a Star Olympic-class sailboat when I was fifteen, all with my dad’s prodding.

Sometime in my teenage years, my dad decided he wanted to build a sailboat and found plans for a full keel, heavy displacement, pocket cruiser. On a family, camping vacation, a know-it-all man we met who owned a Corvette (50-50 weight distribution he bragged) dismissed the plans for the boat my dad liked and suggested a Thunderbird. (It was a much better boat for what my dad planned.)

My dad’s professional life became one of strife. He was commuting to lower Manhattan by car, parking in an alley off Lafayette (Great Jones Alley?), and was at war with his principal, Miss Pepper. It was a mess. My mother was at home in Rocky Point, I was living in Atlanta and all of his kids were out of the house.

At age 62, he retired on a full pension, Social Security and after 13-years of litigation, my mother’s lawsuit settlement. My parents had more money coming in than they had ever had in their entire life. My dad’s third life began.

The average life expectancy of a quadriplegic is ten to twelve years. They die of complications from pressure sores – Chris Reeves is an example. My dad kept my mother alive for 31 years. This was done through complete devotion and attention to detail. It also means enforcing the unpleasant, like keeping her in bed for months at a time until any sores healed.

My mother was a remarkable woman and quite a partner to my father. Their devotion to each other allowed them each to survive.

In 2002, my dad had been retired for thirteen years. Life had been good. He was flying model airplanes and feuding with his club mates. He decided he wanted to have a Thunderbird sailboat. He could moor it in Mt Sinai harbor where I had kept my Star and sail in Long Island Sound.

He found a boat in Toronto and trailered it to his house in Rocky Point. He was 75, ten years older than I am now. The boat needed work: the deck was soggy in places and there were other leaks.

I made him an offer, if I fixed the boat, could I live on it that summer?

Dad, from his reading, knew how to replace the deck coring – we worked from below decks using end-grain balsa. He designed a lightweight structural filler for places that needed filling and, together, we did the beginning of the work while I learned the ropes. Then I took over. The work was enjoyable.

By June, the boat, Taaris, number 1113, built in Canada was ready for the water. My dad paid for all of the expenses, including putting the boat in the water and moorage. I moved aboard and started sailing again after more than thirty years.

I was speaking with my sister, Linda, about this. She said that Taaris was the perfect boat before I fixed it, it was a project that would never be completed. It turned out not to be a worry. My dad, after all these years of wanting to get out onto the water, found he didn’t like sailing.

I lived on the boat every year after that from the beginning of June until Labor day, sailing three or more days per week and riding a bicycle twelve miles round trip to the Port Jefferson Library, which I used as an office.

In 2006, when he was age 78, a woman, coming from the opposite direction on Sunrise Highway, NY27, crossed the double yellow line and hit my dad head-on. At the last moment she tried to get back into her lane and the van my dad was driving hit her car just forward of the A-pillar. She did not survive.

As part of the crumple-zone in his van, the engine moves backward and down. In doing so, it caught his foot requiring amputation below the knee.

His time in the hospital started a routine that continued until he died: Someone with a clipboard walks into his room, looks at him, turns around, and walks out. They then look at the room number and name on the wall, pause, walk in and say, I’m looking for Vincent Juliano. When my Dad replies that he is Vincent Juliano, the person replies, ‘‘you’re fill in the blank years old?’’ It gave my dad great pleasure.

I promise I will write part 2, I promise.

*My sister says, our mother told her, he was fired.

I’m looking forward to reading part 2! After reading this, I feel compelled do the same — write about my family and our lives growing up on Long Island. Will I, though? I should.

I’m having trouble sitting down and doing the work. I think I have been in one place long enough now – a bit of a record across the last bunch of years – that I can do this.

Please do write Part II, and soon. You know, until I read this, I did not know you had lived in Toronto. Funny, as I spent 8 years there from 1976-1984. We’ll have to talk soon.

I did know you went to U of T there. Odd that I did not mention I grew up there – ’58 to ’65. Shirley Wiggans, another commenter, was my next-door neighbor (at age six).

John,

My son Ben texted me your story and I just got thru reading it. Renting from your parents in Rocky Point were some of the best years of my life. I also look forward to reading part two. Sorry to hear of your dad’s passing. Fond memories of your entire family.

We’ve been living in Pittsfield, Me. since 1981. I retired from a career of 41 years of engineering in 2014 to set my son Ben up in the Auto Body Business.

Fondly,

Tom Gilbert

118 Morrill St

Pittsfield , Me. 04967

207/416-7066

t51gilbert@gmail.com

Tom, we’ve been trying to locate you for some time. I’ll contact you directly. How did Ben find this?

Those pics are how I remember your parents….our parents along with the O’Connors and the Reids, are the adults whom, I feel, had the biggest impact on my early childhood. I do not know if we moved first to Willowdale or if your family did, but I recall my Mom saying that our parents did influence each other in that decision. I was just happy to have a friend living close by and was very sad when you moved away.

I, too, am looking forward to part 2 of your family story.

Dear John

Thx for the detailed biography of your Mom and, esp. your Dad!!

My parents were good friends with them and my memories and that of my siblings were always very positive.

It’s amazing the detail with which you can describe their lives. Very happy to read all this and looking forward to part 2. All the best this coming year and take care of yourself.

Big hug for both of you❤️❤️

Loved reading about your parents!!!

They were good friends of my parents.

Your detail about your parents is Amazing.

I wish you both a great New Year and I’m

Really looking forward to part 2 .Big hug for both of you❤️❤️

Thank you. Have you always used Anna, rather than the name I know you by?

My real name is Anna but my nickname is Ankie.

I found this out when I graduated from Ryerson and my Dad asked why Ankie was on my diploma?

I told him that I thought my real name was Ankie!!!

John, I love this! To me this is such an authentisch piece of American history. I am so impressed with your writing, I cannot wait to see part 2! You made an entire era come alive, brillant!

Bettina

Thank you, Bettina. The next post that goes up will be about a friend who died in a boating accident. Not part two. I”ve wanted to write about the dangers of being on the water and that will be the first in that series.

John how Interesting,

our fathers were born the same year but my sister was our first born in ‘54.

It makes me think of my fathers’ life who died in ‘15. He gave me my life long love of sailing.

But that’s a different story

Warren

Warren,

Thank you for commenting. Write about your dad and your parents, also your sailing/sailing industry experience. You are an expert in the circle in which we move.

John I am struck by how the stories of our fathers is so coloured by our own. Our perceptions and realities are overlaid on the impressions we have of their lives and it isn’t until some time later that we see them or hear of them through the eyes of another, a family member or friend. They fill out, become more rounded, or angular as the case maybe. In my case I have never really loved my father. A result of the anger and violence in our home. Many people now say what a wonderful man he is and I agree, NOW! 40 years ago he was very different. The pressure of work and finances and maybe the disappointments of life made him quite different, and my recollections of that time, are of a strict and harsh disciplinarian. How wonderful that we can change. I have found room to forgive him and I can even tell him I love him – though that is from a purely intellectual point of view, there is no corresponding emotional warmth. Only pity for a man slowly fading away, suffering from the inexorable creeping dementia, the result of a succession of strokes. He taught all four of us kids to sail and fostered in me an unmet desire to sail the oceans of the world. I sometimes feel trapped in the circumference of my circumstances. I would be off, if I could be completely selfish, head for the horizon.

“One day when my ship comes in” was a phrase I often heard from my father’s lips. I determined in my heart that Would find my satisfaction and meaning for my life not in the vague hope of something future, but in the solid reality of the here and now.

Thank you for this place of reflection and correspondence. Thanks for opening the door to your heart that we might wander around and meet like souls!

Graeme,

In my own life, there are so many things, some of which lasted a long time, that I would return to change, or fix ‘‘next time.’’ For most of us, there is no next time. Bing Crosby, the singer, got a next time. He raised his first set of kids as a harsh disciplinarian. given the times, we can guess what that means.

Older, as many men do, he married a younger woman and had a second set of kids, these he raised gently and did over what he did wrong the first time.

For some of the things I regret, I did get a do-over, but like Crosby’s older children, my do-over did nothing to fix the wrongs I had made, other than to add, perhaps, some heft to my useless apologies: I learned, I don’t do that anymore, I am doing it better this time.

I’m sorry about your dad and the way it is ending. As one of the wronged, you know it can’t be undone.

Thank you for this intimate, loving portrait of hope and dedication.

Great job writing about your parents, the complexities of growing up, and how our own lived experiences affect our understanding & memories of our parents. Looking forward to the next edition.

Thanks, Dave.

John,

First, let me wish you a Happy and Prosperous New Year filled with much joy and exciting adventures.

What a great story about your Dad and Mother. Looking forward to Part II. You amaze me with your writing skills and your memory of your parents and life events.

Take care my friend and let me know when you are in Atlanta again so we can do lunch.

Don,

First, Have a happy New Year. I’m pleased you’re here to share it with us.

I’ve promised a part 2 and I have started it.

Finally, I should be there in April, though I seem to have promised to be in a few different places in April, so ti will be this spring, if not April. Lunch it is.

John,

I am sorry for the loss of your father. Both your parents have a very special place in my heart . I will always remember them for the big hearts and the how they watched me as a child for the short time we lived in Rocky Point. God Bless and keep up the great work.

Thanks, Ben. I remember you at the house very well.

Time marches on. My dad’s been gone three years, my mother almost fourteen. It is difficult to comprehend the passage of time.

Thank you for reading this. Best.

Dear John.

I am a Reid, Brenda, Donna’s sister.

My sympathy on your Dad’s passing and your Mom’s.

I have fond memories of your parents, the O’Connors, the Woodmans. That time was special to all of them. All of our family were in Montreal and we were just the four of us.

I remember Mrs. Locasto and the beautiful large home your parents bought in Don Mills. I was in awe.

My Mom only went to visit your parents once, I think with Mrs. O’Connor. Your parents would come every few years and my husband Bill and I had them for dinner once in our home. They came as well for Mom and Dad’s 50th wedding anniversary celebration.

Mom always sent your Mom a Christmas gift. Your Dad made us laugh and was larger than life . These are my memories.

I found it hard when Dad was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and passed away from a stroke. Years later Mom was diagnosed with dementia and it was very difficult watching her slip away. I miss my parents a lot.

Your writing is beautiful and I hope to read part II when you have finished it.

Take care John.

Brenda,

How did you find this?

I wrote about your dad once, I thought here, but perhaps to your sister. Your dad came to visit my parents together with Marianne O’Connor. They were two very different personalities, but Mrs. O’Connor spent her time with my mother and your dad with my dad.

On that visit, (when I was in my forties) as an adult rather than as a child I got to know your dad. He was the loveliest of men. I wanted to engineer a way to visit him somehow and get to know him better, but the years passed and I missed my opportunity.

You were very lucky to have him as a father.

Thank you for these so very nice words about my parents. I find I don’t feel loss as something sharp and crushing, but rather as something that leeches slowly over time and when I am distracted. In Mexico, this past month, I felt my father’s passing and my loss acutely when I could not call him to tell him about the places we traveled, the people we met, and getting a car stuck somewhere that sane people would never take a car (just like him).

( I remember that as an engineer your dad wore an iron ring – was it his wedding ring? I’ll write to you with further memories.)